Where is Salinger buried? Where is Salinger buried?

Nowhere. Salinger was cremated. So there is no marker or grave to visit, no memorial on which to lay flowers. After all, who wants flowers when you' re dead? Nobody. |

|

Salinger on Vietnam Salinger on Vietnam

While vacationing in Bermuda with his mother in 1966, Salinger was asked by a pair of dinner guests to justify American policy in Vietnam. “This I could not do,” he later explained, “because our Vietnam policy stinks.”

“Stinks.” It's doubtful Holden Caulfield could have put it any better.

|

|

Salinger, Vedanta, and the mysterious Mary Salinger, Vedanta, and the mysterious Mary

“My roots in Eastern philosophy—if I may hesitantly call them ‘roots'—were, are, planted in the New and Old Testaments, Advaita Vedanta, and classical Taoism…” ~ Seymour - An Introduction

Records show that Salinger became actively involved in Advaita Vedanta while he was completing The Catcher in the Rye. By 1951 he was attending lectures and services at the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of New York and studying under the Center's spiritual leader, Swami Nikhilananda. That year, he wrote enthusiastically to friends on the virtues of Nikhilananda's translation of The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, which he called “the greatest religious book of the century”. In fact, Nikhilananda became more than just Salinger's spiritual mentor. He became the author's confidant and trusted friend. Salinger himself referred to their relationship as one of “respect and affection”.

In July 1952 and again the following year, Salinger attended Swami Nikhilananda's summer seminars at Thousand Island Park where he meditated in the sanctuary of the upstairs room of Vivekananda Cottage, which he considered a shrine. It was there that, I believe, Salinger experienced a spiritual awakening that transformed his work and that resulted in a lifetime of devotion to Vedantic faith.

Today, the Thousand Island Park community is abundant with Salinger lore. Memories of Salinger's time on Wellesley Island are often recounted by the community's older members and have been passed down to each generation since the early 1950's. One persistent story is that Salinger first visited the island in 1950, accompanied by the great zenmaster DT Suzuki, and it was during this early visit that he first encountered Vedanta. Salinger's name does not appear on the Center's official registry for Swami Nikhilananda's summer seminar until 1952, but that does not remove the possibility that he did visit Vivekananda Cottage at Thousand Island Park earlier. In fact, the bend of Salinger's literature toward Vedantic doctrine prior to 1952 implies that he did.

Salinger's sudden interest in Vedanta, in seminars at Thousand Island Park, and perhaps in the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center itself, may not have been purely spiritual, at least in the beginning. Another story told by the Thousand Island Park community asserts that Salinger was dating a young girl named Mary, whose parents owned a summer house on the island and attended the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of New York when home in Manhattan. Salinger's letters of the time lend credence to this story, and although any romance with Mary eventually waned, his devotion to Vedanta endured as the spiritual staple of his life.

Sometimes, God works in mysterious ways.

|

|

The real-life Seymour Glass The real-life Seymour Glass

It was Salinger's mother who inadvertently introduced her son to philosophies from the Far East at an early age. When the Salingers were living on Manhattan's Upper West Side (1928-1932), Miriam became fast friends with a neighbor named Pearl Simon. Pearl had a son two years older than Salinger named Harry. Salinger and Harry Simon became the closest of friends, a relationship that lasted throughout their childhoods and beyond their teenage years. Harry, who may well have been a certified genius, had an unusual preoccupation for a child: he was completely engrossed in Japanese and Chinese culture, literature and verse, and at the age of ten could lecture for hours on the tenets of Taoism and Zen Buddhism.

Salinger was intrigued, especially when Harry was recruited by Townsend Harris High School (one of the most scholastically demanding private schools in the nation) before moving on to Columbia, where he became a candidate for a PhD in Far Eastern Studies at the age of 21 and was offered a fellowship by the University that sent him to Japan where he translated Chinese and Japanese texts to the admiration of veteran scholars. While still in Japan in December, 1940, Harry suddenly died of a brain tumor (or burst aneurism, depending on the account) but would one day be reincarnated onto the written page as Seymour Glass by his childhood best friend.

|

|

The truth behind “A Girl I Knew” The truth behind “A Girl I Knew”

Okay, here I need to roll out some serious humility. Mea culpas aside, in truth, the events surrounding Salinger's time in Vienna and Poland during 1937-38, on the eve of the Anchluss, are less dramatic than has been reported but still fascinating.

The house where Salinger lived in Vienna still stands. The building was home to a prominent Jewish family named Safir--a family Salinger genuinely came to idolize--as well as the staging ground for a teenage romance between young Jerome and a Viennese girl apparently fond of ice skating. The Safirs were business partners with the meat import/export tycoon Oskar Robinson, known throughout Europe as “the King of Bacon”. Based in the Polish city of Bydgoszcz, Robinson was also a business associate of Salinger's father and Jerome's natural sponsor in Europe. When Robinson died in a Vienna casino during Salinger's visit, Jerome was whisked back to Poland (reportedly to take care of Robinson's widow, although I can find no evidence of that) and was on his way back to New York as the Nazis were marching into Austria.

Salinger, whose Austrian working papers designated him as “Catholic”, was not alone in his narrow escape. The Robinsons were also instrumental in rescuing the Safirs. Just as German stormtroopers were closing in on Vienna, the family fled to Poland before quickly moving on to England and the United States. When their properties were formally confiscated by the Nazis during the summer of 1938, the Safirs were at least temporarily safe with the Robinsons in Bydgoszcz. Salinger knew they had made it to safety long before he wrote “A Girl I Knew” but the story may still reflect an actual tragedy. The Safirs had two sons only, leaving the identity and fate of Salinger's Austrian love an unbroken mystery.

|

|

Was Giles Weaver J.D. Salinger? Was Giles Weaver J.D. Salinger?

Here, I risk being tarred and feathered by Salinger purists who recoil in horror over the mere suggestion that Salinger may have been the secret author of the Giles Weaver entries, a series of posts written under a pseudonym that appeared in The Phoenix literary quarterly in 1970 and 1971. The entries were once carried on this site but were removed due to a thunderstorm of recrimination. Since then, I have come to the careful conclusion that Giles Weaver and J.D. Salinger were, in all likelihood, the same.

It's long been assumed that the Giles Weaver entries were either written by Salinger using a pen-name or submitted by a deliberate imposter mimicking Salinger's style. Such questions often clarify with time. We can certainly evaluate true authorship better now than The Phoenix ever could in 1971—and that clarity only increases with time and information. An imposter (for lack of a better term) who was largely guessing events would have invariably slipped up by offering facts that eventually proved to be untrue or by omitting information that later turned out to be vital.

The Giles Weaver notes are remarkably clean of such errors--and deliberately so. By and large, whoever wrote them was exceedingly careful not to spill specific facts that might trip them up or expose them one way or the other. However, there is a glaring exception contained in the next to last installment. There the writer suddenly—and uncharacteristically--offers a list of uniquely definitive facts regarding his father. None of these facts correspond to Salinger's father.

But rather than disqualifing Salinger as being the author, this curious collection of errors actually has the opposite effect. It is extremely unlikely that anyone outside of the small Salinger circle would have had much detailed information about Salinger's father in 1971. So why, after being so careful throughout, did the writer offer these facts so close to end of an otherwise remarkably successful ruse? Logic suggests that a clever imitator would not have attempted such a bold lie so late in the game. While in contrast, that is exactly the type of maneuver Salinger would have employed, especially if he tired or thought better of the Phoenix correspondence and sought to remove suspicion that he was, indeed, its author.

There are other reasons, too, why I lean toward the opinion that Salinger authored the entries. Most are contained in the Phoenix 's text, and many are circumstantial; but not all. Salinger's contemporary personal correspondence confirms that he was painting with vigorous regularity while the Giles Weaver entries were being submitted. It was a pastime that Salinger kept extremely private, so much so that readers may be surprised by his hobby even today. Among the paintings Salinger created in 1970 was one he titled "Interplanetary Intercourse", the same phrase used by Giles Weaver to name a drawing he sent to The Phoenix that year. |

|

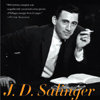

While my new work demands that I step away from (what had become) my comfort zone, a portion of my interests will always be invested in the life and work of J.D. Salinger and I will continue to update this site whenever events warrant. Three years after Salinger's death and there is still no word on his unpublished manuscripts. (My bounce-rate just leapt exponentially.) However, a few intriguing articles of information have come to light in recent months that are worth sharing, especially as we mark the third anniversary of Salinger's passing.

While my new work demands that I step away from (what had become) my comfort zone, a portion of my interests will always be invested in the life and work of J.D. Salinger and I will continue to update this site whenever events warrant. Three years after Salinger's death and there is still no word on his unpublished manuscripts. (My bounce-rate just leapt exponentially.) However, a few intriguing articles of information have come to light in recent months that are worth sharing, especially as we mark the third anniversary of Salinger's passing.

Salinger on Vietnam

Salinger on Vietnam

The real-life Seymour Glass

The real-life Seymour Glass  The truth behind “A Girl I Knew”

The truth behind “A Girl I Knew”  Was Giles Weaver J.D. Salinger?

Was Giles Weaver J.D. Salinger?